The Plague outside Eyam

Disease was rampant in the 17th century. In England, people anxiously read the Bills of Mortality, published every week, which listed the number of deaths and their causes. Plague was the most feared disease of all: people died of it every year, and the Black Death pandemic – which had killed nearly one third of Europe's population (20 million people) in the 1300s – still lived on in folk memory.

The plague was terrifying because it struck so swiftly. Victims died within days, in agony from fevers and infected swellings. It spread at a horrifying rate, too, and could ravage a town or even a city within weeks. With no cure, the authorities relied on drastic methods to contain it. Many continental countries built large plague hospitals – 'pest houses' – to hold victims, but England preferred cheaper local solutions. Its 'plague orders' decreed that victims should be shut into their own houses and left to die.

The first case of what was to become the Great Plague of London was discovered in April 1665, in St Giles-in-the-Fields, a built-up area just to the west of the walled City. By the end of May, 11 people had been infected – enough to cause alarm. Victims were shut into their houses and the doors were nailed shut and marked with a large red cross. Nurses were hired to take in food and carry out basic care, and guards were set on watch to make sure that the sick (or their families) did not escape.

But the weather was unseasonably hot and the plague bacillus throve. People fell sick across St Giles; then cases broke out within the City walls and spread across the districts of Whitechapel, Westminster and Southwark. An exodus began. The rich left the city and most of the physicians went with them. Many clergy left too. The king and his court decamped to Salisbury. The poor, on the other hand, were forbidden to leave London. Seen as carriers of the disease, they were turned back at the boundaries.

The people tried desperately to protect themselves. They sniffed herbs and nosegays to drive out the bad air. They fasted and prayed. Apothecaries did a brisk trade in preventative potions and religious and magical amulets. Meanwhile, the Privy Council closed inns and lodging houses. Many markets were cancelled and street stalls banned. Forty thousand dogs and 80,000 cats were slaughtered. This last move actually made things worse, as the plague- carrying rats were now free of predators. By the end of July, more than 1,000 Londoners were dying each week.

During August, the plague reached many provincial towns, including Salisbury, forcing the court to move on to Oxford. East Anglian towns were particularly hard hit – when Cambridge University closed down, 23-year-old Isaac Newton was forced to return home to Lincolnshire where he devised calculus and considered the nature of gravity. York was also badly affected: the grassy embankments still beneath its walls are the sites of plague pits.

Nowhere suffered on such a grand scale as London, where normal life had virtually stopped. Thousands of families were locked into their homes, the well along with the sick, waiting to die. A gruesome new plague economy developed, as parishes hired their own residents to carry out the plague orders. People became 'examiners', who found and reported the sickness; 'scavengers' and 'rakers', who cleaned the streets; and 'watchers' who guarded them. Women were paid to go into houses as 'nurses' and as 'searchers', to find out who had died.

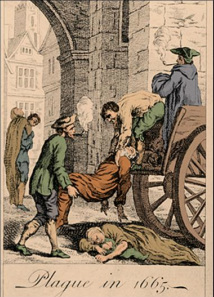

Bells tolled continually, announcing new deaths. In September, matters worsened. Thousands died in the first week and carts went round London, collecting the dead bodies and taking them to newly dug plague pits on the capital's edges. Ten thousand people camped on boats anchored in the Thames, hoping to escape the contagion. Fires were lit outside every sixth house and kept burning for days and nights, in the hope that the fumes would drive away the infected air.In the third week of September, 8,297 official plague deaths were reported. The real number was certainly higher – throughout the epidemic, families concealed deaths for fear of being shut in, and in the chaos, many simply died unrecorded.

But as the weather turned colder, the rate of infection began to fall. In October, people started returning to London, and during the winter, trade gradually resumed and London's streets became busy again. The epidemic was not yet over: new cases continued to appear in London and many provincial towns were badly stricken in 1666. But London was a living city once more, if a diminished one. The Bills of Mortality list 68,576 plague victims in the capital. The true figure is probably nearer 100,000.

To find the website where this information was taken from, please click this text!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The video to the left talks about the Plague in London in 1665, Eyam was not the only place infected by the plague, in fact it affected many areas all over Europe, killing thousands!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------